Premenstrual Syndrome

Understanding PMS from Puberty to Menopause

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is a monthly condition that afflicts many women ranging from young girls (sometimes even before menses) to women approaching menopause. Many women struggle for years with changing symptoms as their reproductive systems evolve through life stages. However, understanding and taking measures to treat the underlying causes of PMS provide options to help minimize its debilitating symptoms while simultaneously promoting overall improvements to physical health and emotional well-being.

Symptoms of Premenstrual Syndrome

Symptoms of PMS vary from woman to woman; furthermore, their symptoms may change over time. Many PMS symptoms may be associated with other conditions. However, the symptoms truly related to PMS typically occur after ovulation, during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle (beginning approximately 14 days before menstruation), and cease at menstruation or shortly thereafter.

The symptoms of PMS are varied, with over 150 identified. The more common ones include:

| Physical Symptoms | Mood-Related Symptoms | Cognitive Symptoms |

| Acne | Mood swings | Difficulty concentrating |

| Breast tenderness | Irritability | Decreased efficiency |

| Weight gain or abdominal bloating | Tension | Confusion |

| Appetite changes | Anxiety | Forgetfulness |

| Fatigue | Tearfulness | Headaches |

| Dizziness | Restlessness | |

| Hot flashes | Anger or rage | |

| Nausea or vomiting | Loneliness | |

| Muscle aches | Depression | |

| Pelvic pressure | Sadness | |

| Constipation | Social avoidance | |

| Palpitations | Emotional outbursts | |

| Changes in vision | Violent urges |

Practitioners find that most women’s symptoms tend to fall into one of four typical subgroups:

- PMT-A (anxiety)

- PMT-C (cravings)

- PMT-D (depression)

- PMT-H (hyperhydration, such as bloating and weight gain)

The most consistent characteristic of PMS is that its symptoms recur regularly, coinciding with a woman’s menstrual cycle.

While symptoms tend to be cyclical, even the patterns of that cycle may vary. In PMS: Solving the Puzzle, Linaya Hahn identifies five patterns of symptoms, occurring primarily within the luteal phase but varying in timing and intensity (see Patterns of PMS Symptoms). Some women experience symptoms throughout the luteal phase, some only during the few days immediately preceding menstruation, and some experience more than one peak period of severe symptoms.

It is not only the type of symptom but also the intensity or severity that can vary dramatically from woman to woman, and even for the same woman throughout her cycle. For some women, PMS is merely an annoyance; for others, it is so severe that they cannot even get out of bed. About 5% of women suffer from Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD), a more severe form of PMS predominated by mood symptoms that are almost completely disabling.

Causes of Premenstrual Syndrome

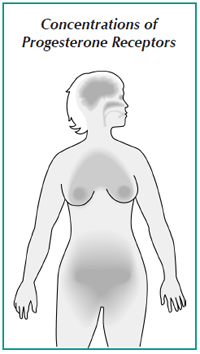

Because it occurs only in women who are still menstruating, most researchers agree that hormone imbalances may contribute significantly to the occurrence or severity of PMS symptoms. The levels of the hormones associated with menstruation fluctuate widely during a woman’s cycle. In Once a Month: Understanding and Treating PMS, Dr. Dalton notes that estrogen hormone levels vary throughout the cycle, and that blood levels of progesterone are much smaller during the first half of the cycle and then suddenly rise at ovulation to levels that are far greater (see Concentrations of Progesterone Receptors).

Because it occurs only in women who are still menstruating, most researchers agree that hormone imbalances may contribute significantly to the occurrence or severity of PMS symptoms. The levels of the hormones associated with menstruation fluctuate widely during a woman’s cycle. In Once a Month: Understanding and Treating PMS, Dr. Dalton notes that estrogen hormone levels vary throughout the cycle, and that blood levels of progesterone are much smaller during the first half of the cycle and then suddenly rise at ovulation to levels that are far greater (see Concentrations of Progesterone Receptors).

The Role of Progesterone

Our understanding of the association between progesterone and PMS has developed along with our ability to measure hormone levels. Previously, many researchers and practitioners believed that it was the amount of progesterone in the bloodstream that affected PMS symptoms. With more advanced analysis tools (such as radioimmunoassays), researchers discovered that PMS sufferers do not necessarily have low progesterone levels.

Molecular biology advances have allowed researchers to explore how progesterone is absorbed into the nucleus of cells, leading to a greater understanding of progesterone receptors. As it turns out, having a sufficient amount of the progesterone hormone does not guarantee that there is an adequate number of receptors, nor that those receptors are working properly.

Dr. Dalton relates how Bruce Nock, et al. “showed that progesterone receptors do not transport progesterone molecules into the nucleus of cells if adrenaline is present,” such as during times of stress or when glucose levels drop—times during which PMS symptoms are also exacerbated. Additionally, progesterone receptors do not transport artificial progestogens (also called progestins) to the cell nucleus. This may help explain why they have not been found effective in treating PMS-related symptoms.

The locations of progesterone receptors are also the primary locations of the most common PMS symptoms, Dr. Dalton observed. She thinks this is no coincidence, and that the cause of PMS may be linked to progesterone receptors. For example, Dr. Dalton notes that, in women, the largest concentration of progesterone receptors is in the limbic area of the brain–the area that controls emotions and has been identified as the center of rage and violence.

Other parts of the body have concentrations of progesterone receptors, including:

- The cells lining the brain, which are involved in headaches, a very common PMS symptom

- The breasts, which may explain why breast tenderness is also a common PMS symptom

- The womb, ovaries, and fallopian tubes, which go through significant premenstrual changes

- The optic pathway, which may account for changes in ocular pressure during menstruation

- The nose, nasal passages, and lungs, which may explain a tendency for premenstrual asthma, rhinitis, sinusitis, or laryngitis

According to Dr. Dalton, “the widespread distribution of progesterone receptors in different target cells explains the numerous different symptoms of PMS.”

Neurotransmitters

Dr. Thomas Shiovitz and senior research scientist Edyta Frackiewicz, PharmD, hypothesized that PMS may be related to neurotransmitter function. They contend that some women may have “an underlying neurological vulnerability to normal fluctuations” in menstrual hormones. Their central nervous system reacts differently to these normal hormonal fluctuations, altering brain neurotransmitters and leading to PMS symptoms.

Drs. Shiovitz and Frackiewicz found that women with PMS tend to have abnormal neurotransmitter function during the luteal phase of their menstrual cycle, particularly concerning serotonin. Serotonin is a vital neurotransmitter that decreases at ovulation, and has been linked with:

- Depression

- Moodiness

- Irritability

- Anger

- Aggression

- Poor impulse control

- Increased carbohydrate cravings

Serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as Prozac have shown some effectiveness in reducing the symptoms of severe PMS-related mood disorders and PMDD.

Hahn states that PMS is caused by “correctable irregularities in the normal brain chemistry changes that accompany ovulation.” She notes that our bodies produce serotonin from tryptophan, an essential amino acid. (“Essential” meaning it must be replaced daily in our diet since our bodies do not produce it. Fortunately, tryptophan is available in many foods, such as turkey, milk, eggs, fish, and soybeans.)

During menstruation, when serotonin levels are low, the body may trigger an insulin surge to get tryptophan to the brain. This may be indicated by craving sweets (including foods such as pasta, bread, or alcohol) which are quickly converted to blood sugar. Tryptophan generally increases serotonin levels, but there are many factors related to the efficiency of that conversion:

- While many women crave sweets, snacks with aspartame (an artificial sweetener) contain phenylalanine that competes with the tryptophan.

- Vitamin B6 is necessary for converting tryptophan to serotonin, and which may explain why it helps suppress some women’s PMS symptoms.

- Sodium is necessary to keep serotonin active, which may be why salt cravings are also common during PMS.

- Light, a switch that triggers the conversion of melatonin to serotonin, may also be linked to PMS. Hahn sees a connection with Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD, especially among women with primarily mood-related PMS symptoms.

Lifestyle Factors

Drs. Shiovitz and Frackiewicz observed that women who eat a high-sugar diet have an increased risk of PMS. They found that women who consume large amounts of caffeinated beverages or alcohol tend to have more severe symptoms. Severe premenstrual discomfort was also associated with deficiencies in:

- Calcium

- Magnesium

- Manganese

- Vitamin B6

- Vitamin E

In addition to diet and exercise, other lifestyle factors such as stress influence PMS symptoms. Researchers note that day-to-day stress is more strongly associated with PMS than a major life event. The build-up of daily stressors such as family and job responsibilities may help explain why women in their 30s and 40s tend to have more severe symptoms than their younger counterparts. Stress-related symptoms may build to the point that they become intolerable.

Diagnosing Premenstrual Syndrome

Dr. Dalton defined PMS as “the recurrence of symptoms before menstruation with complete absence of symptoms after menstruation.” She claimed that the most important criteria for an accurate diagnosis are the cyclical nature and timing of symptoms, relative to menstruation, rather than which specific symptoms occur. Therefore, if symptoms are not restricted to the luteal phase, they may indicate another condition.

Because symptoms are so varied in type, timing, and severity, PMS is difficult to pinpoint. For this reason, most practitioners will ask patients to keep a monthly symptom chart to track daily symptoms for three or more consecutive months. Even with rigorous charting and notes, PMS may not be recognized as the predominant condition or misdiagnosed as another condition.

Before offering a diagnosis, healthcare practitioners will often try to rule out conditions such as:

- Anemia

- Thyroid imbalance

- Yeast infection

- Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS)

- Diabetes

- Endometriosis

One or more of these conditions are often present in women suffering from PMS symptoms. For example, Hahn reports that early research indicated that one in six women with PMS symptoms also had a thyroid imbalance.

Other disorders may be associated with symptoms that are severe and primarily mood-related:

- Major depression

- Generalized anxiety

- Panic attacks

- Bipolar disorder

Some PMS symptoms, such as breast tenderness, headache, and sleep disturbances, are also associated with perimenopause.

In some cases, a phenomenon called “menstrual magnification” may make it more difficult to accurately diagnose PMS. This occurs when certain conditions are intensified during the luteal phase, such as:

- Migraine headaches

- Seizures

- Asthma

- Allergies

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS)

Specific criteria for a diagnosis of PMDD are even more rigorous than diagnosing PMS. According to these criteria, PMDD symptoms must:

- Be primarily related to mood

- Persist for at least one year

- Be serious enough to interfere with a woman’s work, social activities, and relationships

Although PMDD can be diagnosed by a psychiatrist, a biological basis may be missed.

Treating Premenstrual Syndrome

Lifestyle Modifications

Most practitioners begin treatment with a two- to three-month trial of lifestyle modifications. Recommendations of lifestyle changes may include:

- Making dietary changes such as reducing or eliminating sugar, salt, caffeine, chocolate, dairy products, and alcohol

- Eating smaller, more frequent meals of a diet that is low in trans fats (partially-hydrogenated vegetable oils) and high in fiber

- Stopping smoking, which is known to contribute to symptoms

- Getting regular, moderate exercise, such as walking

- Regulating sleeping

- Reduce stress or explore stress management techniques

When initiating any lifestyle changes, it’s important to chart symptoms to see what effects, if any, they have on PMS symptoms. Although these lifestyle changes take time and perseverance, they often result in a broad range of benefits. In addition to relieving PMS symptoms, these types of changes may lead to improvements in overall physical and mental health.

Medications

If lifestyle changes do not provide enough symptom relief, healthcare practitioners typically turn to antidepressants, primarily SSRIs such as Prozac, as the first line of treatment. This treatment is especially common for women with predominantly mood-related symptoms. Anti-anxiety medications such as alprazolam (Xanax) are sometimes prescribed to treat irritability, anxiety, and milder forms of depression associated with PMS.

While the results of these drug therapies may sound encouraging, each woman should take into account the pros and cons of such treatments. Antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications tend to have a wide array of potential side-effects that may turn out to be just as troublesome as the PMS symptoms they are intended to treat. For example, prolonged use of SSRIs is associated with diminished bone density, which may lead to osteoporosis and a higher propensity to falls.

Supplements

A wide variety of over-the-counter, PMS-specific supplements are available that may offer symptom relief. These supplements typically include:

- Calcium

- Magnesium

- Manganese

- Vitamin B6

- Vitamin E

Many women report broad symptom relief simply from taking vitamin B6 supplements.

Herbal supplements may be beneficial for treating some symptoms, but they have not been fully-evaluated for treating PMS. Examples of these types of supplements include:

- Evening primrose oil

- Black cohosh

- John’s-wort

- Garlic tablets

As with all therapies, it is best to discuss any supplement you are taking with your healthcare practitioner to make sure it is not interfering with other medications or treatments.

Hormone Therapies

Oral contraceptives are frequently suggested as a possible PMS treatment because they suppress ovulation, usually with a combination of estrogen and progestin (a synthetic progesterone replacement). However, many women report a worsening of their PMS symptoms when taking oral contraceptives, or they experience side-effects worse than the original PMS symptoms.

Dr. Dalton notes that severe PMS sufferers tend to have high levels of estrogen hormones and may benefit from bioidentical progesterone therapy. (Women with high estrogen levels tend to have fewer symptoms as they approach menopause, while other women typically need estrogen therapy for menopausal symptom relief.) Bioidentical progesterone is fairly inexpensive, has few (if any) side-effects, and has been effective in reducing or relieving many PMS symptoms.

The typical treatment protocol requires adjusting dosages throughout the cycle. However, Dr. Dalton emphasizes that clinicians must also take into account the behavior of progesterone receptors when determining the appropriate dosages. After the first dose, subsequent doses need to be much higher to achieve the same reaction in the progesterone receptor cells.

Conclusion

Primary goals in treating PMS are to reduce or eliminate symptoms, restore daily function, and optimize overall health. Many women struggle for years with changing symptoms as their reproductive systems evolve through life stages. However, understanding and taking measures to treat the underlying causes of PMS provide options to help minimize its debilitating symptoms.

Connections is a publication of Women’s International Pharmacy, which is dedicated to the education and management of PMS, menopause, infertility, postpartum depression, and other hormone-related conditions and therapies.

This publication is distributed with the understanding that it does not constitute medical advice for individual problems. Although this material is intended to be accurate, proper medical advice should be sought from a competent healthcare professional.

Publisher: Constance Kindschi Hegerfeld, Executive VP – Women’s International Pharmacy

Editor: Julie Johnson – Women’s International Pharmacy

Writers: Carol Petersen, RPh, CNP; Laura Strommen – Women’s International Pharmacy

Illustrator: Amelia Janes – Midwest Educational Graphics

Copyright © Women’s International Pharmacy. This newsletter may be printed and photocopied for educational purposes, provided that your copy (or copies) include full copyright and contact information.

For more information, please visit womensinternational.com or call 800.279.5708.

For more information, please visit womensinternational.com or call 800.279.5708.

Women’s International Pharmacy | Madison, WI 53718 | Youngtown, AZ 85363